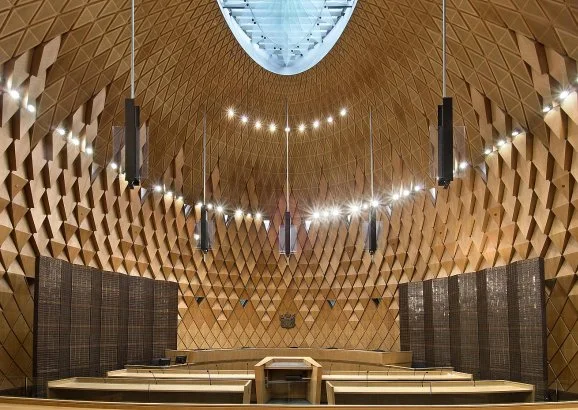

The photo accompanying this post is of the award-winning interior of the New Zealand Supreme Court. If it looks expensive, that's because it was. It was officially opened in January 2010, and built at a cost of $80.7 million. If you are a party to a case in the Supreme Court, that's expensive too. It means that you are likely to have had a hearing in the High Court, then an appeal to the Court of Appeal, then the hearing of an application for leave (permission) to appeal to the Supreme Court. For the run-of-the-mill commercial case, that's likely to mean legal costs incurred which would pay the rent on an average commercial office space for years...

The Supreme Court is the final appeal court in New Zealand. And it's where the case I reviewed in July (Site visits are dangerous territory) was finally determined yesterday. The Supreme Court declined Kyburn Investments leave to appeal from the decision of the Court of Appeal, bringing to an end what will have been a very expensive piece of litigation.

As a quick reminder, the case was all about a site visit during a rent review arbitration which went wrong. The arbitrator had undertaken the site visit in the presence of a representative of Beca, without the knowledge or consent of Kyburn. During the site visit the arbitrator and the representative of Beca had a "limited" discussion about the building, which was "not of particular materiality to what was in issue in the arbitration".

Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal had held that the site visit constituted a breach of natural justice. But the Court of Appeal declined to set aside the arbitrator's award on the basis that although there had been a breach, it did not have a material effect on the outcome of the arbitration. The High Court Judge's view was broadly the same.

In the Supreme Court Kyburn argued that once a breach of natural justice had been found then the "default position" should be that the award should be set aside, and that the discretion not to set aside the award should only be exercised in the clearest of cases where substantive justice is done despite the breach.

The Supreme Court found that there was "no appearance of a miscarriage of justice" in the approach taken by the Court of Appeal. The Judges noted that the Court of Appeal decision was reached after a "close examination of the award and the basis given for it". The Court of Appeal correctly took into account that the case involved a rent review valuation where the focus was narrow and the considerations "largely obvious and standard", and was entitled to find that no material impact followed from the irregularity. As a result, the Supreme Court declined leave to appeal.

So, what does that all mean? Ultimately the challenge to the arbitrator's award came to nothing, but at what cost? Although I don't know the amounts involved, I wouldn't be at all surprised if the amount spent on the case far exceeded the difference between the parties in the original rental valuations.

The lesson from the case has to be, for arbitrators, don't ever undertake a site visit in the presence of only one party. For litigants it would have to be to resolve your disputes at the earliest stage possible, and apply your hard earned money to further your business interests, rather than to the development of the law of arbitration! Even though that may happen in a very nice building.